With elections coming, the junta still fears the specter of Thaksin Shinawatra.

CHIANG MAI, Thailand—A specter is haunting Thai politics: the specter of Thaksin Shinawatra.

On Friday, the country’s political scene was upended by the shock announcement that a senior member of the royal family was running in national elections set for March 24. The candidacy of Princess Ubolratana, the eldest sister of King Maha Vajiralongkorn, was news enough: The 67-year-old actress and Instagram star is the first royal to enter party politics since the end of the absolute monarchy in 1932. Much more explosive was who she was representing: a party closely allied to Thaksin Shinawatra and his sister Yingluck, two former prime ministers who were democratically elected and then ousted in military coups (he in 2006, she in 2014).

The announcement set up an electoral showdown between the magnetic princess and Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha, the dour and thin-skinned former general who has led Thailand since the military’s seizure of power in 2014 and is running as a prime ministerial candidate. But just as Thai observers were digesting the implications of the royal candidacy—Did it violate election laws? Would opponents dare to criticize a member of the royal family?—the king intervened, declaring that his sister’s entrance into politics was “inappropriate” and unconstitutional. The pro-Thaksin Thai Raksa Chart party quickly confirmed it would comply with the royal command, and Thailand’s Election Commission on Monday formally disqualified Ubolratana from running, saying that members of the royal family should be “above politics.” The bombshell candidacy had lasted barely 48 hours.

With any discussion of the royal family chilled by Thailand’s harsh lèse-majesté law, which carries jail terms of up to 15 years for insulting the monarchy, commentary on these remarkable developments by local analysts has been muted. This has not stopped a frenzy of online speculation, as observers of Thai politics have sifted through the shrapnel searching for answers to the question: What comes next? Pravit Rojanaphruk, an award-winning journalist for Thailand’s Khaosod News, described Friday as “arguably the most intriguing day since absolute monarchy ended 87 years ago.”

The princess’s announcement has brought back to the surface the bitter enmity that has animated Thai politics for nearly two decades.

The conflict pits the supporters of Thaksin, a billionaire telecommunications mogul elected to office in 2001, against what one scholar has termed the “network monarchy”: an enmeshed military-royalist elite that includes senior bureaucrats, Thai aristocrats, and business interests close to the palace.

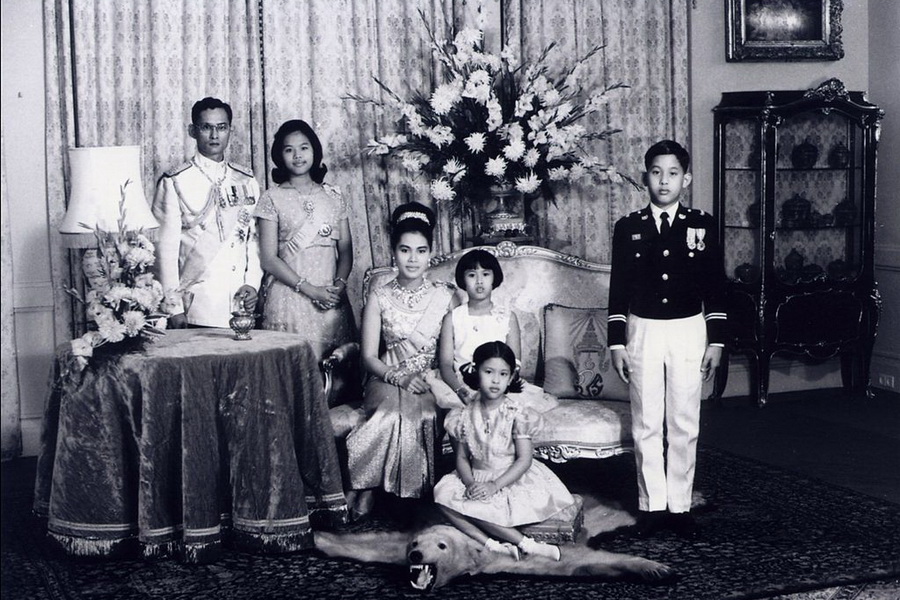

Looming behind this struggle is the power of King Vajiralongkorn, who acceded to the throne in late 2016, following the death of his father, the revered King Bhumibol Adulyadej. While the monarchy has played a ceremonial role in Thai politics since 1932, the institution wields considerable symbolic power. So far, the Thailand specialist Eugénie Mérieau has written, the new king has been more forceful than his father in asserting his royal vetoes and prerogatives, including pushing for changes to the role and composition of the Privy Council, a powerful advisory body, in a bid to assert his power over the “network monarchy” that surrounds him. (Many Thais assumed that Ubolratana would not have announced her prime ministerial run without her brother’s blessing; his response on Friday indicates that this likely wasn’t the case.)

The princess’s announcement has brought back to the surface the bitter enmity that has animated Thai politics for nearly two decades.

While a military coup in 2006 chased Thaksin from office and into exile, it failed to curtail his wild popularity among rural Thais, whom he had won over with populist policies such as universal health care and access to microloans. Like Banquo’s ghost, Thaksin continues to haunt the banquet of the Thai elites: His proxy parties, backed by his “red shirt” supporters, have swept the last three general elections, including a landslide victory that brought his sister to power in 2011.

When the military seized power in 2014—the 19th coup or attempted coup in Thailand since 1932—Prayuth justified the takeover on the grounds that it would stabilize Thai politics, safeguard the monarchy, and bring the people “sustainable happiness.” Yet in preparing to hold long-awaited elections, Prayuth and his allies face the reality that any free and fair process would likely simply re-elect the latest avatar of the Thaksinite movement. This is one reason the return to civilian rule has been repeatedly delayed. It also explains some of the actions that Prayuth—a self-described “soldier with a democratic heart”—has taken during his time in power.

In 2017, the National Council for Peace and Order (as the junta calls itself) wrote and passed a new constitution giving the prime minister a huge amount of power. The constitution gives the junta the right to select the 250 members of the Senate, meaning that Prayuth’s party and its allies could potentially name the next prime minister if they win as few as 126 out of the 500 seats up for grabs in the lower house. There are other reasons to doubt a free and fair election on March 24. The U.S.-based organization Human Rights Watch has argued that Thailand’s media outlets “face intimidation, punishment, and closure if they publicize commentaries critical of the junta and the monarchy, or raise issues the NCPO considers to be sensitive to national security.”

Facing these obstacles, the Thaksin camp’s nomination of a royal family member was a radical—even desperate—bid to out-trump the military-royal alliance. It zeroed in on the main political claim of the junta and its conservative supporters: that they are defending a hallowed throne against the crude, corrupt, and supposedly anti-monarchical sentiments of Thaksin and the red shirts. “This is much more momentous than, say, [Britain’s] Prince Harry running for office,” Tom Pepinsky, a professor at Cornell University, wrote in a commentary shortly after the announcement of Ubolratana’s candidacy.

The princess has always been a royal outlier. In 1972, while studying at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, she married an American citizen and subsequently relinquished her royal titles. As a result, she has largely avoided the ceremonial obligations that occupied the life of her three siblings. She was also not shy about maintaining her ties to Thaksin following his overthrow in 2006; the two were seen together at the soccer World Cup in Moscow last summer.

If successful, her nomination would have produced an irresistible electoral synthesis, a fusing of royal sanctity to the overwhelmingly rural, working-class populism that propelled Thaksin and his sister to power. Given the political sensitivity surrounding the monarchy, it was also highly risky. “Thaksin took a massive gamble in putting the princess forward as a candidate,” said George McLeod, a Bangkok-based political analyst.

The gamble now looks likely to backfire. Puangthong Pawakapan, an associate professor at Chulalongkorn University, described Thaksin’s move as a “serious mistake” and predicted that the Thai Raksa Chart party “is likely facing a dissolution”—possibly under Thailand’s election law, which prohibits parties from employing the monarchy or its imagery in their campaigns. Sure enough, on Sunday, a royalist political activist announced that he was filing a petition seeking the party’s dissolution. McLeod said that that junta might also choose to target the Pheu Thai Party, Thaksin’s other electoral vehicle.

The dissolution of either party would inflame further the bitter rivalries of Thai politics, possibly pushing enraged red shirts to return to the streets. “Thaksin’s case to his supporters has always been that they aren’t represented by the elite,” McLeod said, “and I haven’t seen anything that undercuts that message.” Even if one of the pro-Thaksin parties were to prevail, it would find itself at the mercy of a raft of military-dominated oversight bodies—and of the ever-present threat of monarchical power.

Whatever the result on March 24, it is unlikely to deliver either the democracy desired by many Thais or the stability promised by the junta. “Military rule has brought superficial stability, but many Thais are bitterly resentful of military rule and the political meddling of the palace,” said Andrew MacGregor Marshall, a journalist and lecturer at Edinburgh Napier University who was the first to break the news of Ubolratana’s candidacy last week. “The dramatic events of Friday have left the country even more polarized than ever.”

Published in Foreign Policy, February 12, 2019