I’m sitting in my hotel off Bui Vien Street in central Saigon, exhausted from the early start and aching in the legs from today’s walk. I’m stealing wireless, achingly slow, from somewhere nearby; and my Windows taskbar is in a state of constant excitement, informing me, every few seconds, of connections granted and denied. My new 7000-đông copy of Kanye West’s Graduation grinds and scrapes in the disc drive, slowly trickling data into my iTunes library. The familiar smell — a blend of chlorine, cooking oil and motorbike exhaust — drifts up from the street outside my balcony and the sun sinks behind a thicket of television aerials and satellite dishes.

I set off this morning to find a small bookstore in Cholon, Saigon’s Chinese district, which I discovered there in 2006. It was nothing more than a hole in the wall, piled high with dusty cast-offs from the post-’75 era, including volumes of Marx and Lenin, Russian textbooks, engineering manuals and a few dog-eared English paperbacks. It was here, strangely, that I first came across Gore Vidal’s Washington D.C. I also bought an old English-Russian map of Saigon from the early 1980s and a children’s story book entitled Bac Ho Kinh Yeu (‘Uncle Ho Respects and Loves’), describing Ho Chi Minh’s lifetime crusade against the imperialists and — judging by the watercolour on the cover — his enduring affection for preteens. I couldn’t for the life of me remember where the store was, except that it was across the road from the offices of the Saigon Cigarette Company, with a ten-foot concrete cigarette casting its monstrous phallic shadow over the parking lot.

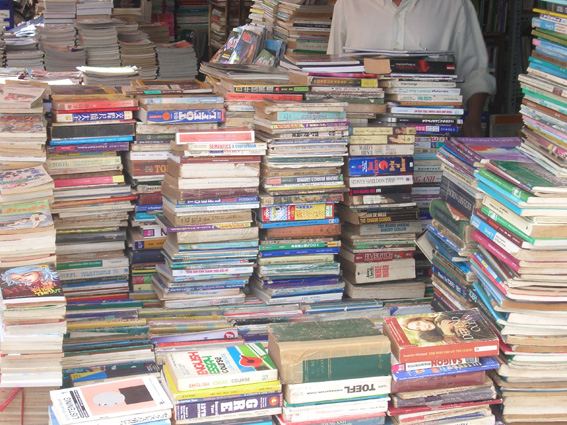

After spending about two hours winding through the backstreets of Cholon trying to find the right street, I tried a different tack. Searching on Google.vn, I found the address to the cigarette company and gave it to a moto taxi, who had me there in about five minutes. To my satisfaction, the book store (Hieu Sach Minh, 23 Phan Nhan Ton, Q.5) was still there, a riot of paperbacks piled under a slumping awning. Inside, I was like a kid in a candy store. Old books were stacked from floor to ceiling, roughly ordered by language and subject. There was little in the way English fiction, except for a few third-rate Star Wars novels; but towards the back of the store I came across a treasure trove of antique non-fiction and ended up walking out with more than I could carry.

- Book sellers in Phan Nhan Ton Street, District 5.

To start with, I bought a three-volume hardback series entitled Minority Groups in the Republic of Vietnam, compiled in 1966 by order of Harold K. Johnson, US Army Chief of Staff. As well as information on the ethnic minorities of the Central Highlands and the khmer krom of the Mekong Delta, the book has a detailed entry on the Binh Xuyen criminal syndicate, who operated the lion’s share of prostitution and gambling rackets in 1950s Saigon. A band of bandits and river pirates from the region south of Cholon, the Binh Xuyen rose to political and military prominence during the last years of French colonial rule. By the time of the French departure in June 1954, the group had gained control of Saigon’s police force and civil administration; it also controlled the opium trade, much of the city’s fish and charcoal commerce, and several hotels and rubber plantations around the capital. In the countryside, it maintained a string of semi-autonomous fiefs, exacting taxes from the local peasants and maintaining mutually-hostile relations with both the communist Viet Minh and the new government of president Ngo Dinh Diem. But for more than a year after coming to power, Diem waged a war against the Binh Xuyen, and, by the end of 1955, the syndicate had all but collapsed. From this point on, Saigon’s vice rackets were jointly controlled by freelance gangsters and, until his assassination in 1963, by Diem’s own extended family.

Fodor’s 1969 Guide to Japan and East Asia (stamped ‘Property U.S. Army’ on the inside cover) advises the prospective visitor to post-Diem Saigon: ‘This divided nation’, writes the author, ‘is the most dangerous country in the world for today’s visitor. Saigon is definitely not the place for a tourist’. Of course, if danger was your thing, there was plenty of fun to be had in wartime Saigon: One could spend a ‘nauseating’ night crawling the bars and ‘gaudy fleshpots’ of old Cholon, ‘notorious city of the demimonde‘; or, for a subtle change of scene, the nightclubs of District 1, where crones from the first Indochina War were ‘rehabilitated’ to handle the growing demand of American and other ‘Free World’ soldiers. There were also sites to be seen in Nha Trang and Hue, although the latter, ‘sometimes under shellfire’ and fresh from the ravages of the 1968 Tet Offensive, was ‘best avoided’.

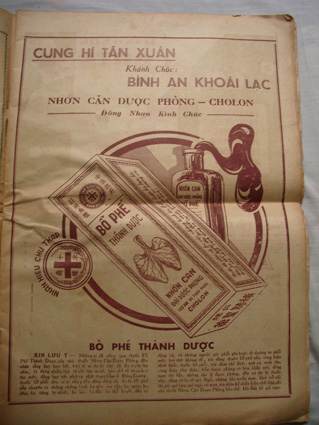

An old Guide Historique Des Rues De Saigon, written in 1943 under the Vichy administration of French Indochina, gives a glimpse of the city in the somnolent age of high colonialism, when Graham Greene smoked opium in Rue Catinat and the tricolor fluttered over the wedding-cake Hôtel de Ville. André Baudrit, historian and committed imperialist, makes his dedication to the ‘Amiraux-Gouverneurs (1839-1879), les véritables fondateurs de SAIGON, ville Française’, and describes, in magniloquent passages, the glorious ‘conquet de Cochinchine’. Under a pile of engineering manuals, I also found a Vietnamese tabloid magazine (Doc Thay) from 1952, complete with news about the Hearst mansion, anti-communist propaganda, and photos of actress Jane Russell striking rakish poses against a backdrop of bougainvillea.

An old Guide Historique Des Rues De Saigon, written in 1943 under the Vichy administration of French Indochina, gives a glimpse of the city in the somnolent age of high colonialism, when Graham Greene smoked opium in Rue Catinat and the tricolor fluttered over the wedding-cake Hôtel de Ville. André Baudrit, historian and committed imperialist, makes his dedication to the ‘Amiraux-Gouverneurs (1839-1879), les véritables fondateurs de SAIGON, ville Française’, and describes, in magniloquent passages, the glorious ‘conquet de Cochinchine’. Under a pile of engineering manuals, I also found a Vietnamese tabloid magazine (Doc Thay) from 1952, complete with news about the Hearst mansion, anti-communist propaganda, and photos of actress Jane Russell striking rakish poses against a backdrop of bougainvillea.

Before leaving with my stack of books, I asked the store owner for maps (ban do), unsure whether he would understand my pidgin Vietnamese. Apparently so: he disappeared upstairs only to appear five minutes later with an armful of dusty relics from the Diem era. For half an hour, we unfurled old road maps, US army aviation surveys and, most bizarrely, a briefing on Vietnam’s water resources from the Army Engineer Training School at Fort Belvoir, Virginia. Many of these maps were fraying and eaten away by damp, some literally coming apart in my hands as I unfolded them. Among other odds and ends, I came away with a French carte routière of Quang Ngai province, inscribed with blue biro; and, intriguingly, a military ‘joint operations graphic’ of Cambodia’s Kampot province, seemingly from the 1980s. I left the store reluctantly, my fingers blackened by dust and newsprint. The entire purchase — five maps, five hardbacks and a magazine — came to just US$40.

5 comments

Yosh says:

Mar 7, 2008

An enviable story, enviably told, my boy.

Hope you’re well.

Jessica Anne Friedmann says:

Mar 8, 2008

I still find it amazing that we must have been staying in roughly the same quarter a few years ago and had no idea of each other’s existence. And then, there we both were, eying each other off from either side of a two-page spread.

I’m not sure whether you’re travelling north or bumping on down to Phnom Penh next, but there are some great little bookshops in Hoi An, as well as possibly the best patisserie in Vietnam.

I am very, very envious of those maps. The only thing I seemed able to find in Cholon was gold jewellery and friend pig faces on sticks. Ah well, next time…

mary k says:

Mar 9, 2008

I’m so jealous. Secondhand bookshops are my ultimate weakness. There’s nothing like that feeling of unearthing buried treasure.

Take care over there, Strangio. Your conversation is missed.

Calvin T says:

Apr 2, 2008

Thanks for sharing a good story, Strangio.

Interested in book trading ? Please drop me a line. Thanks.

Francis Enright says:

Sep 28, 2009

The famous novelist, Graham Green, who wrote “The Quiet American”, read a travel book called “Dragon Apparent”, by Norman Lewis, about travelling in French Indochina, which then comprised Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. It was from reading “Dragon Apparent” that Graham Green became interested in travelling to Indochina in the 1950s.

The young women in Vietnam are very beautiful.