Protecting the buildings of bygone eras is no easy task in rapidly changing Old Dhaka.

DHAKA—Walking through the centre of Dhaka’s old city, Taimur Islam stops to lament the loss of another historical building. From a plastic binder, the architect produces pictures of a stately colonial mansion, built around the turn of the 1900s, that has recently been reduced to a pile of rubble. In the shaded lot where the building once stood, a few walls remain, their cream-coloured stucco work standing out proudly from piles of shattered brickwork.

“A lot of old buildings have been destroyed over the last year,” Islam says, shaking his head.

Such scenes are common in the old parts of Bangladesh’s capital, a rapidly growing megacity of 15 million people. As the city swells with poor rural migrants, developers eager for land have targeted Old Dhaka – a sprawling suburb of Mughal-era relics, noble colonial buildings and the improvised add-ons of more recent times.

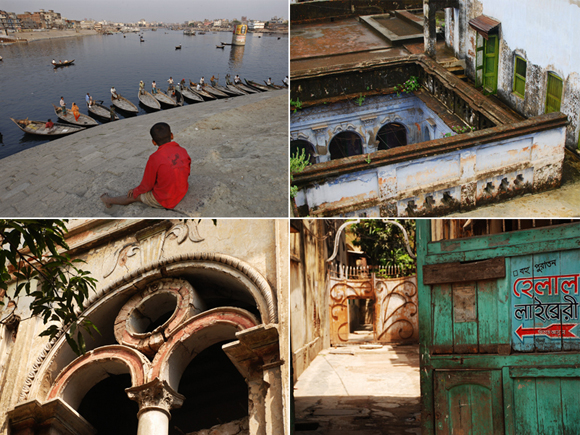

Old Dhaka’s rich architectural legacy dates from the 1600s, when the city was founded as the Mughal capital of Bengal. After 1793, when the British East India Company took control of the region, the city prospered and many fortunes were made. Armenian and Hindu merchants built ornate palaces and mansions across the city, many commanding views over the Buriganga River, which runs through its heart.

As the city fell into decline following the Partition of 1947, most wealthy Bengalis abandoned Old Dhaka’s bazaars for less-crowded areas with better amenities, leaving behind an eclectic feast of architectural styles.

At the dizzying centre of the old city is the iconic Shankaria Bazaar, an area named after the shankari – or Hindu artisans – whose ancestors still operate from the cramped workshops in the surrounding alleys, filling the narrow byways with kites, brasswork, engravings and technicolour posters of Hindu deities. Hindu Street, as it is known locally, remains the epicentre of Bangladesh’s Hindu community, coming vibrantly alive during the annual festivals of Diwali and Durga Puja.

Across the city, crumbling mansions stand in various states of picturesque decay, dwarfed by a new generation of concrete apartment blocks. In Armanitola – once home to the city’s Armenians – grand old houses sit behind high brick walls, their iron gates slumping resignedly inwards. Families camp inside the empty shells, setting bright saris to dry in the sun on rusted balcony railings. A small Armenian church, built in the 1760s, acts as a rare sanctuary from the noise and bustle of the city outside; its weathered marble headstones bearing the names of long-departed merchants and notables.

Many structures in Old Dhaka have been repurposed as warehouses and machine works. In one century-old building, a man works a grinding machine in near darkness; nearby rooms, lit by fluorescent lights and strung with jerry-rigged electrical wiring, act as kitchens, break rooms and sleeping quarters for the workshop staff.

In the Chowk Bazaar district, two brick caravanserais stand amid the colour and cacophony of the marketplace. Originally constructed in the 1700s as way stations for travelling merchants, their cavernous interiors are now used as flour mills and storage warehouses.

The Buriganga takes centre stage in the drama of renewal and change that has Dhaka in its grip. Riding a boat on its dark churning waters, along with thousands of merchants and cross-river commuters, is a hair-raising experience.

A fruit-seller in Old Dhaka. (Sebastian Strangio)

According to Islam, the city is nearing a point of no return in the preservation of its architectural history. The pace of development in the area – one of the most densely populated regions on Earth – is rapid. “It has not only destroyed the urban fabric, it has also destroyed the environment,” Islam says. “Most of these places, they don’t function as proper neighbourhoods any more.”

In 2004, Islam and his wife – also an architect – formed the Urban Study Group (USG), an organisation campaigning for the preservation of the city’s old buildings. To raise awareness of the issue, Islam conducts twice-weekly walking tours of Old Dhaka, guiding visitors through the winding back lanes, walled gardens and dilapidated buildings of the former Mughal capital. The proceeds from the tours go to fund the USG’s campaign to have sections of the old city listed as protected areas, and to restore historically significant buildings.

The couple were moved to start their campaign after a building collapse in Shankaria Bazaar killed 19 people, leading the government to propose levelling a strip of old structures. Since then, the USG has created an inventory of about 3,000 historical buildings in Old Dhaka that it claims are under threat. With a dense population in the old city, public safety has often been a handy justification for pulling down buildings.

“You know the Chinese saying,” says Islam, “if you want to kill a dog, give it a bad name.”

The issue came to a head in June last year, when a raging fire tore through the Nimtoli district of Old Dhaka, killing at least 125 people. Police described it as the worst blaze in the country’s history and, even though Nimtoli is an area of new multistorey apartment blocks, it has given developers fresh pretexts for the removal of old buildings.

“The developers have become absolutely restless. They want to go ahead with the demolition of everything,” Islam says.

There are some positive signs, however. The United States embassy in Dhaka has provided funds for the restoration of one historic building in the old city and the Asian Development Bank has promised to bankroll the restoration of five structures in Shankaria Bazaar. Islam says he received support from government officials when he suggested a scheme to create a market for development rights. Under the plan, owners of historical properties could “sell” their right to develop as compensation for preserving their old buildings.

It’s too soon to say whether such an approach will be adopted, but Islam remains hopeful that parts of central Dhaka – like many European capitals – will see a gradual renewal and that restaurants, hotels and other businesses will give new life to the city’s colonial relics.

“There are no reasons why we can’t make these buildings safe for continuous use,” he says.

[Published in the South China Morning Post, November 20, 2011]