Indonesia’s former dictator looms in bronze over the entrance to the small museum set amid the palm trees and rice fields of central Java. Depicted in a military uniform and peaked officer’s cap, he radiates calm authority over the village of his birth.

To many, the New Order regime that Suharto led from 1967 to 1998 is a byword for corruption and repression on a grand scale, including a brutal campaign of anti-communist purges that historians describe as one of the worst atrocities of the 20th century.

As president, Suharto jailed and exiled his political enemies, and crippled democratic institutions. In 2004, the antigraft organization Transparency International described Suharto as the most corrupt leader on earth, claiming that he embezzled as much as $35 billion while in power. But in a country where open discussion of his rule remains taboo, the General Suharto Memorial Museum celebrates him as a kindly father and heroic nation-builder. To some, this is a rewriting of history.

Housed in an imposing walled compound in Suharto’s hometown, Kemusuk, a short drive outside the city of Yogyakarta, the museum opened in 2013. It was built by Suharto’s younger half brother, Probosutedjo, who grew wealthy under his sibling’s rule, but in 2003 was tried and convicted of corruption. He was sentenced to four years in jail and ordered to pay back $10 million to the Indonesian state.

Gatot Nugroho, the museum’s director, said Probosutedjo, now 87, wanted to counter the criticisms of Suharto that emerged after he was forced from power amid mass pro-democracy protests in 1998.

“He built the museum so the Indonesian people could learn the positive side of Suharto’s rule,” Mr. Nugroho said.

He described the strongman as an independence hero and “father of development,” who safely navigated his country through the tumult of the Cold War.

On a recent visit, schoolchildren gazed at the foundations of the home where Suharto was born in 1921, and the well where he hauled water as a youngster. Visitors posed for photos next to a bust of the “great general,” while a music system blared New Order anthems, including the song “Suharto Is Our Father.”

Across the street, small shops sold cold drinks and souvenir T-shirts featuring an elderly Suharto smiling, above these words: “How are you doing, bro? It was better in my time, right?”

The Indonesian dictator, who died in 2008, is still largely revered in this quiet town of dusty back streets and shaded Javanese cemeteries. Locals spoke of the economic development brought by the New Order and the gifts bestowed on the area by the Suharto clan.

Biyono, 82, who runs a small shop near the museum selling cold drinks and Suharto T-shirts, said the New Order introduced electricity and paved roads to the area and took a harsh stance on crime. “If there was a criminal then, Suharto ordered them to be shot directly,” he said.

The New Order did notch some significant achievements. Suharto oversaw an economic boom, drastically reducing poverty and expanding access to health care and education. In 1984, Indonesia achieved self-sufficiency in rice production — a milestone that is celebrated at the museum.

But the museum displays are silent on the darker side to the story.

Dioramas and panels focus on Suharto’s roles in the independence struggle against the Dutch and in prying the region of Papua from colonial rule in the early 1960s. Video screens show footage of the dictator giving speeches and greeting foreign leaders, including Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher.

Mami Lestari, 38, a niece of Suharto’s who lives in Kemusuk, said that despite the excesses of some of her uncle’s cronies, he always stood up for the little people.

“Maybe right now people’s salaries are higher, but there is a bigger gap between the rich and the poor,” Ms. Lestari said.

In the last presidential election in 2014, the tycoon Aburizal Bakrie, the presidential nominee of Suharto’s old Golkar party, ran a campaign that leaned heavily on New Order nostalgia.

Across Java, posters and T-shirts appeared in which an elderly Suharto encouraged the public to remember how much better it was “in my time.” Golkar and members of the leader’s family have also petitioned the Indonesian government to grant him the title of “national hero,” so far unsuccessfully.

The effort to rehabilitate the New Order has been vigorously opposed by activists like Bedjo Untung, who spent nine years imprisoned without trial in the 1970s. “It is completely wrong,” said Mr. Untung of the museum. “It is manipulated history.”

Mr. Untung heads a group that seeks to open up discussion of the anti-communist massacres that Suharto presided over in late 1965 and early 1966 — a crucial episode in his ascent to power.

The killings were provoked by a failed coup against then-President Sukarno by a group within the Indonesian armed forces, during which six generals were kidnapped and executed. Suharto and other top commanders quickly quashed the uprising, pinning it on the Indonesian Communist Party.

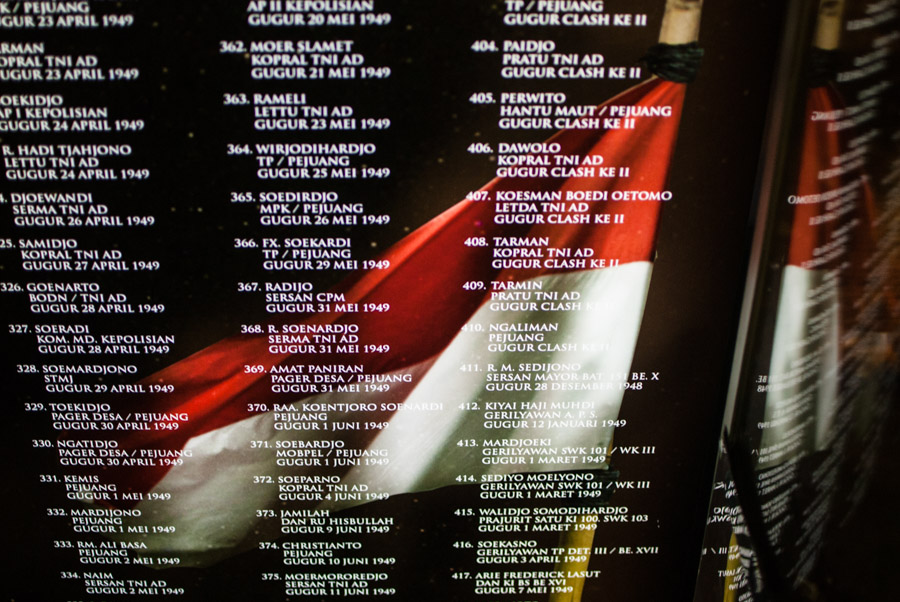

Security forces and local vigilantes then hunted down people suspected of being communists. An estimated 500,000 people were killed, many of them innocent, and thousands more were locked up without trial.

A large section of the museum is given over to displays justifying the crackdown. Illuminated panels show gory photos of the bodies of the six executed generals, next to a life-size photo of Suharto wearing military fatigues and sunglasses.

There is no mention of the many innocent people killed. Mr. Nugroho, the museum’s director, acknowledged that some killings took place in 1965, but put them down to the spontaneous anger of the Indonesian people.

Baskara T. Wardaya, director of the Center for Democracy and Human Rights Studies at Sanata Dharma University in Yogyakarta, said it was “predictable, and to a certain extent understandable” that a museum built by Suharto’s family would present a one-sided version of history.

But when it comes to the 1965-66 events, he said, the museum mostly reflects the official story that is still told in Indonesian schoolbooks and state museums.

For Mr. Untung, the fact that a monument to Suharto’s legacy could exist while silence prevailed about the killing of thousands of innocents showed that the battle over Indonesia’s history will be drawn-out.

“Suharto is not a legitimate hero,” Mr. Untung said. “If he was a hero, my struggle will be useless.”

Published in The New York Times, August 13, 2017

Reporting for this story was supported with the kind support of the International Reporting Project.