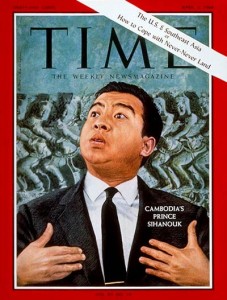

PHNOM PENH – Cambodia’s former king Norodom Sihanouk, the charismatic monarch whose name was synonymous with the struggles and upheavals of his country for more than six decades, died in Beijing on Monday at the age of 89. Sihanouk, who abdicated the throne in 2004, had been dogged by poor health for years and had suffered a variety of illnesses, including cancer, diabetes and hypertension.

Prince Sisowath Thomico, a royal family member and advisor to the current king, said Sihanouk died of a heart attack early Monday morning. “He had been very weak since the beginning of the year,” he said. The present monarch, King Norodom Sihamoni, has flown to Beijing to retrieve Sihanouk’s body, accompanied by Prime Minister Hun Sen and other senior officials. Thomico said the body is expected to return to Cambodia for a traditional royal funeral within a few days.

During a storied life stretching across more than 60 years, Sihanouk saw his country transformed from French colony to a nascent modern state before it was consumed in the fires of civil war and the cruel communist dictatorship of the Khmer Rouge. He served as king, prime minister, communist figurehead, leader in exile, and then as “constitutional king” until his retirement in 2004.

“The whole Cambodian people will mourn his death,” Thomico said. “Most of all, he will be remembered as the father of Cambodian independence.”

Throughout his career, Sihanouk’s chameleon-like changes masked an unwavering conviction that he had a unique ability to foster national reconciliation during an era of great upheaval for Cambodia. In his biography of the monarchy, Milton Osborne described Sihanouk as a “politician much more concerned with achieving a limited number of practical goals than with developing a coherent political philosophy” – something that confused and frustrated Western observers.

Throughout his career, Sihanouk’s chameleon-like changes masked an unwavering conviction that he had a unique ability to foster national reconciliation during an era of great upheaval for Cambodia. In his biography of the monarchy, Milton Osborne described Sihanouk as a “politician much more concerned with achieving a limited number of practical goals than with developing a coherent political philosophy” – something that confused and frustrated Western observers.

Norodom Sihanouk was born in Phnom Penh on October 31, 1922, and grew up in ornate surroundings in French colonial Indochina. In 1941, after the death of king Sisowath Monivong, the French authorities placed Sihanouk on the throne, expecting the chubby 19-year-old prince to be malleable.

After his first uncertain years, however, Sihanouk grew into a powerful political figure, outmaneuvering the French authorities and helping to win Cambodia’s independence from France in 1953. In 1955, constrained by what he later termed the “terrible servitude and crushing responsibilities” of kingship, Sihanouk abdicated the throne in favor of his father to take a more active role in politics.

His political movement, the Sangkum Reastr Niyum, leveraged his popularity among Cambodia’s predominantly rural population and set Cambodia on its first steps as a modern nation, building up the education system and expanding the country’s agrarian economy.

As the Cold War deepened and neighboring Vietnam slipped into the maelstrom of civil war, Sihanouk attempted to keep his country neutral, dancing delicately between the United States and the communist bloc. Sihanouk was a founding member of the non-aligned movement – through which he struck up his life-long friendship with North Korea’s reclusive leader Kim Il-sung – but he accepted US aid and maintained relations with communist China. Premier Zhou Enlai was a close personal friend.

The country’s “golden age” – as many Cambodians would later remember the 1950s and 1960s – was dominated by the personality of Sihanouk, who combined bravura statesmanship with stints as a film-maker, jazz musician, socialite and playboy. (Like many of his royal forbears, Sihanouk had dozens of concubines and fathered a total of 14 children).

To outside observers, Sihanouk’s rapid political shifts and well-cultivated dilettantism made for an often bewildering mix – the descriptor “mercurial” quickly became compulsory in journalistic copy – but Sihanouk maintained that he was motivated throughout by a single consistent aim: “the defence of the independence, the territorial integrity and the dignity of my country and my people.”

Though often depicted in foreign news reports as a fairytale kingdom steeped in timeless tradition, rule under Sihanouk’s modernized form of feudalism left little room for dissent. He outmaneuvered his parliamentary opponents, convincing (or forcing) many to abandon their parties and join his own.

Those who held out were ruthlessly pursued by the prince’s security forces. Chief among these was Cambodia’s nascent communist movement, which Sihanouk famously dubbed the “Khmers Rouges”, led by Saloth Sar, later to emerge from obscurity under the nom de guerre Pol Pot.

Fluid loyalties

Fluid loyalties

By the mid-1960s, Sihanouk’s diplomatic high-wire act, designed to keep Cambodia out of the Vietnam War, had started to backfire. Domestic opposition mounted. Convinced that the Vietnamese communists would eventually prevail over the US-backed South Vietnamese regime, Sihanouk unwillingly acquiesced to the transport of communist supplies along the “Ho Chi Minh trail” through eastern Cambodia and up from the port of Sihanoukville.

This inflamed the anti-communist and anti-Vietnamese opposition and added to the discontent around the regime’s widespread corruption and growing economic mismanagement. In 1969, the US unleashed a bombing campaign against the communist supply lines in Cambodia, by 1973 devastating large swathes of eastern Cambodia and killed tens of thousands of rural Cambodians.

Eventually, in March 1970, a small clique of military officers – led by General Lon Nol and a royal rival, Prince Sisowath Sirikmatak – overthrew Sihanouk while he was abroad, threw their lot in with the US, and proclaimed a republic. From his new exile in Beijing, where he was given a residence and comfortable stipend, Sihanouk raged against the coup plotters and controversially threw his support behind his former enemies in the Cambodian communist movement.

With the prince at their head, the Red Khmers attracted a wave of rural support and, supported by the Vietnamese communist forces, eventually defeated Lon Nol’s corrupt and incompetent government. The Khmer Rouge, led by Pol Pot, marched into Phnom Penh on April 17, 1975. They immediately emptied the cities and embarked on a radical communist experiment that led to the deaths of an estimated 1.7 million people from execution, starvation and overwork. As he feared, Sihanouk, the formal head of state of “Democratic Kampuchea” until 1976, “was spat out like a cherry pit” by the Khmer Rouge. He became a prisoner, confined to an empty palace in an empty city, and fell into a deep depression.

But instead of turning against Pol Pot when the regime was overthrown by the Vietnamese military in early 1979, Sihanouk flew to the UN General Assembly in New York to denounce Hanoi’s intervention. In 1982, he became head of an awkward coalition of nationalist, republican and Khmer Rouge elements that opposed the new Vietnam-backed regime in Phnom Penh. Throughout the 1980s, the Prince travelled the world and held lavish soirees at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in an attempt to rally diplomatic support for the resistance.

But Sihanouk was to play a key role in the eventual solution to the Cambodian conflict through the brokering of the Paris Peace Agreements, which were eventually signed in October 1991. A month after the signing of the accord, he returned triumphantly to Phnom Penh as the head of a UN-backed interim authority that presided over elections held in May 1993. Sihanouk had little respect for the UN mission that descended on Cambodia during 1992-93, proffering and withholding his support via a string of petulant faxes dispatched from his residences in Beijing and Pyongyang.

The 1993 election was won convincingly by Sihanouk’s son, Prince Norodom Ranariddh, largely by appealing to the deep reservoir of support for Sihanouk and the memories of pre-revolutionary peace and stability. However, Sihanouk forced his son to accept a power-sharing relationship with Hun Sen, the pre-existing prime minister, whose Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) still controlled the Cambodian administration. Sihanouk was re-crowned king and, after several attempts to form a new government under his own presidency, settled grudgingly into his role of monarch who, according to the constitution adopted in 1993, “reigns but does not rule”.

The 1993 election was won convincingly by Sihanouk’s son, Prince Norodom Ranariddh, largely by appealing to the deep reservoir of support for Sihanouk and the memories of pre-revolutionary peace and stability. However, Sihanouk forced his son to accept a power-sharing relationship with Hun Sen, the pre-existing prime minister, whose Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) still controlled the Cambodian administration. Sihanouk was re-crowned king and, after several attempts to form a new government under his own presidency, settled grudgingly into his role of monarch who, according to the constitution adopted in 1993, “reigns but does not rule”.

From the mid-1990s, Sihanouk remained aloof from Cambodian politics, spending most of his time in Beijing or Pyongyang. Cut off from day-to-day politics, Sihanouk nonetheless retained great moral authority, sparring with Hun Sen (who ousted his co-prime minister and rival Ranariddh in a bloody coup de force in July 1997), and continuing to play an important, though oft-times distant, role in Cambodian public life.

In the role of mediator, Sihanouk helped broker power-sharing deals after both the 1998 and 2003 elections which marginalized his son Ranariddh and strengthened the position of Hun Sen. King Sihanouk was also an avid blogger avant la lettre. Before his retirement and after, he posted on his website regular missives, written out in beautiful cursive French, which communicated his acerbic thoughts and opinions about Cambodian politics and its personalities. He also kept up his range of non-political enthusiasms, including film and music.

In October 2004, frustrated by the aftermath of a year-long political deadlock that paralyzed Cambodia’s government, Sihanouk again abdicated the throne in favor of his son Norodom Sihamoni. In retirement, Sihanouk spent little time in his country, remaining in Beijing for medical treatment but his portrait continued to hang from public buildings alongside those of king Sihamoni and his wife, queen Monineath.

Sihanouk also increasingly came to support his former rival Hun Sen, describing his CPP-dominated government in 2009 as “the younger sibling” of his own pre-revolutionary regime. It may be the wily Hun Sen, prime minister now for nearly three decades, who will in time be seen as Sihanouk’s true successor.

[Published by Asia Times Online, October 15, 2012]

2 comments

Roxanne Landry says:

Jul 2, 2013

Former king and leader of Cambodia, Norodom Sihanouk was crowned in 1941. He further consolidated his power in the 1950s before he was toppled by a US-backed coup in 1970 and was exiled to Beijing. He later returned and supported the Khmer Rouge but was eventually put under house arrest by the communist regime. Sihanouk regained the throne in 1993. In 2004, he abdicated due to illness and left the throne to his son. On October 15, 2012, Sihanouk died of a heart attack at age 89 in Beijing.

សុខ ខេមរា says:

Sep 6, 2013

មនុស្សគ្រប់រូបរមែងមានកំហុស ដែលមិនអាចជៀសវៀងបាន។