On Easter Sunday 1967, Jim Thompson, a prominent businessman and Bangkok expatriate, disappeared while on holiday in Malaysia’s Cameron Highlands. The 61-year-old American left his bungalow to take a solitary hike in the hills and never returned.

In the weeks and months that followed, the media were transfixed by the fate of the man known as “the silk king”. All manner of psychics, mystics, jungle fighters and snake-oil salesmen arrived in Malaysia to help local police “solve” the Thompson mystery.

Four decades on, the riddle of the American’s death, like a small-scale version of the John F Kennedy assassination, continues to inspire conspiracy theorists and amateur sleuths. The United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) bumped him off to silence his criticisms of US policy in Vietnam, goes one theory; others claim he committed suicide or was devoured by wild animals.

Today, Thompson is best remembered for the global silk empire he built in Thailand in the 1950s and 1960s and which still bears his name as a Thai luxury brand today. His sprawling home in Bangkok, filled with Southeast Asian objects d’art that Thompson collected during his ramblings across the continent, is one of the country’s top tourist destinations. It was there, silk-clad guides inform visitors, that Thompson entertained Eleanor Roosevelt, wife of US president F D Roosevelt, US author Truman Capote and countless other notables on their sojourns to the Far East.

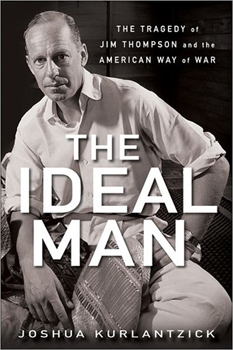

The Ideal Man: The Tragedy of Jim Thompson and the American Way of War, a new book by Joshua Kurlantzick, seeks to fill in some of the blanks in this carefully curated legend. Kurlantzick, a Southeast Asia expert at the Council on Foreign Relations in Washington DC, does not dwell on the riddle of Thompson’s disappearance. He does hazard an educated guess that Thompson was killed by a jealous rival businessman from Bangkok, though there is little in the book that will satisfy those hunting for a definitive answer.

This is probably just as well, since there are several other books that recite the speculations and riddles ad infinitum, and as Kurlantzick notes, the full truth will probably never be known. Instead, the author, through interviews with many of Thompson’s surviving friends and colleagues, focuses on Thompson’s rocky and controversial hand in the political intrigues of post-World War II Thailand – a period that would prove pivotal to the eventual escalation of US military involvement in Vietnam.

Agent of hope

James Harrison Wilson Thompson was born in 1906 into a US East Coast society family rich in both money and military achievement. (His grandfather was James Harrison Wilson, a noted Union general in the American Civil War).

Trained as an architect, Thompson’s career got off to a slow start. After a soporific spell in the Delaware National Guard, Thompson joined the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the forerunner to the CIA, in late 1943, serving with distinction in France, Italy, Algeria and Morocco. Following the war, he was posted to Thailand, then a hotbed of anti-colonial ferment. He was nearly 40 years of age.

In the late 1940s, the French were struggling to wrest control of their Indochinese colonies from the rising anti-colonial movement led by Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh, the beginning of a long, bloody struggle that would end in the defeat and humiliation of the colonialists at Dien Bien Phu in 1954. While with the OSS, Thompson established extensive contacts with the Vietnamese, Lao and Cambodian fighters opposing French rule and came to realize the US had a unique opportunity to court the new nationalist forces.

Like many in the “elite men’s club” of the OSS, Thompson saw that the Viet Minh and its counterparts were more nationalist than communist. Idealistically, he hoped for an America that would use its power “to build democracy in the region, that could distinguish between local grievances and global communism, and that inspired Asians as a liberator, not as a new colonizer”.

Indeed, during the First Indochina War, Ho Chi Minh’s life was probably saved by an OSS medic who injected the communist leader with quinine as he lay dying of malaria in the Vietnamese jungle, according to one account cited by Kurlantzick.

But the window of opportunity was narrow. As the Cold War hawks gained ascendancy in the Eisenhower administration, any US support for “communists” – whatever their coloration – became anathema. Instead of building bridges with Ho Chi Minh, who quoted the US Declaration of Independence when he asserted his own country’s independence in mid-1945, Washington followed Paris into the quagmire.

Kurlantzick writes the policy shift had a strong personal dimension for Thompson. Many of his friends in Thailand, including former prime minister Pridi Banomyong, were exiled or killed by the succession of US-backed military strongmen who ruled Thailand into the 1970s.

In his outspoken criticisms of US policies – often delivered to bewildered guests at his famous soirees – he also alienated many of his US government contacts. During the 1950s and 1960s, the CIA and Federal Bureau of Investigation both launched investigations into Thompson’s supposed “anti-American” sympathies.

Disillusioned idealist

The war also laid bare his own idealized image of Thai society. Kurlantzick shows the extent to which the “silk king” persona was an act that Thompson put on to disguise not only his increasing disillusionment with US policy in Southeast Asia, but also the growing realization that he would always be an outsider in his beloved Thailand.

In many ways, Thompson was the old “Asia hand” par excellence, fleeing from his failed marriage and the tedium of life as an architect in New York to an idealized vision of life in the unspoiled Far East. This extended to his silk business, which managed to lift thousands of cottage silk farmers out of poverty.

By the 1960s, however, this facade had begun to fade and “the silk king”, despite his glitzy social life and flourishing business, had grown increasingly embittered and depressed. As Kurlantzick writes, Thompson lamented Bangkok’s transition from the languid riverine capital of the postwar era to the asphalted metropolis that grew up under US patronage; at the same time, his Thai rivals in the silk business grew increasingly resentful of the foreigner who had made a great success of a “traditional” Thai pursuit.

“He had a kind of idealized image of Thailand, of himself as the protector of the ‘real’ Thailand,” said one of Thompson’s old friends, “and he didn’t like giving that image up”.

The author contrasts Thompson with his fellow American expatriate Willis Bird, a freelance intelligence operative who, though skeptical of turning back the communists in Indochina, nonetheless grasped the opportunity to build a personal empire of influence.

At the onset of the 1960s, Bird played a major – and largely unacknowledged – role in the “secret war” in Laos, the covert arming of tens of thousands of Hmong tribesman as a bulwark against the advances of the Vietcong.

By the time of his disappearance, the once-idealistic Thompson had begun to resemble Fowler, the jaded foreign correspondent from Graham Greene’s The Quiet American. Like Thompson, Fowler was deeply skeptical of the reckless good intentions of policymakers in Washington, symbolized by Greene in the bright-eyed CIA agent Pyle. In fleshing out the complex individual at the center of the “silk king” myth, Kurlantzick underlines the many opportunities the US government had to turn away from the tragic war in Indochina.

The Ideal Man, like Greene’s famous novel, ultimately leaves the reader on a plaintive note, at the foot of a mountain of war dead, with a keen awareness of history’s paths not taken. The tragedy of Thompson and the American way of war is probably best summed up by Philippe Baude, an old friend quoted by Kurlantzick: “[Y]our time is over, your era is disappearing in front of you, but you are still alive, and you know that you have been an engineer of change, but of change that wasn’t what you wanted. There is a certain deep sadness in that.”

[Published by Asia Times Online, November 4, 2011]

2 comments

The legend of ‘Silk King’ Jim Thompson | Correspondent's Corner says:

Nov 14, 2011

[…] Sebastian Strangio has more. function fbs_click() {u=location.href;t=document.title;window.open('http://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u='+encodeURIComponent(u)+'&t='+encodeURIComponent(t),'sharer','toolbar=0,status=0,width=626,height=436');return false;} function twitter_click() {u=location.href;t=document.title;window.open('http://twitter.com/share?url='+encodeURIComponent(u)+'&t='+encodeURIComponent(t),'sharer','toolbar=0,status=0,width=626,height=436');return false;} This entry was posted in Misc and tagged Jim Thompson, Thailand. Bookmark the permalink. ← Dengue Fever at The FCC Phnom Penh […]

The legend of ‘Silk King’ Jim Thompson - FCC says:

Dec 2, 2013

[…] Sebastian Strangio has more. […]